HALTING THE MARCH OF TIME

This is the story of how a unique news program that scored six Top 50 seasons - two in the Top 20 - over a ten year run on three networks was nearly killed once, revived to new popularity, then permanently killed by corporate bungling. It's the story of The March of Time.

It began shortly after World War I when young Henry Luce and Briton Hadden were college pals in charge of the Yale Daily News. There they came up with the idea to create a weekly news magazine, (originally called Facts), which would present the top stories of each seven-day period in a concise, well-written style appealing to the tastes of the modern reader.

Their first edition of Time, appeared on newsstands during the first week of March, 1923. It sold 12,000 copies, mostly through the direct mail campaigns of their first hire, Roy E. Larsen, 23, who had built a reputation in college for turning The Harvard Advocate, an undergraduate magazine, into a surprisingly profitable publication. With Larsen fanning Time’s promotional flames, circulation doubled by the end of 1923 and hit 70,000 a week in 1924.

Larsen became Luce's junior partner when Hadden died suddenly in 1929. He was chiefly responsible for growing the company’s initial investment of $86,000 into a publishing empire valued at $1.69 Billion when he retired 56 years later at age 80. (1) He was also among the first to embrace other media for their promotional value to increase his magazines’ circulation. He was a willing listener when Fred Smith, Station Manager of WLW/Cincinnati paid him a visit in 1928 and proposed that Time join forces with the station to prepare weekly newscast scripts up to 15 minutes in length based on the magazine’s contents. Larsen obtained reluctant permission from a skeptical Luce and Time’s “Newsreel of The Air” began on WLW September 3, 1928. (2)

Other stations around the country which, like WLW, were shut out of news sources by the newspaper controlled wire services, asked to share in Time’s scripts. The magazine’s advertising agency, Batten, Barton, Durstine & Osborne was more than happy to distribute them, along with source credits for the magazine. The requests began to snowball and by September, 1929, the agency began to record the weekly scripts distribute the transcriptions to over 100 of America’s 600 stations.

Time’s circulation continued to grow and passed 150,000 a week in 1931 when WLW’s Smith approached Larsen with another idea. Radio news was still in its infancy and remote broadcasts of news events as they happened were rare. Smith proposed taking the radio program to a new level with dramatic recreations of current events and the reactions to them by actors impersonating the voices of the persons involved. The concept was entirely new, uniquely bold and, if treated properly, would truly result in a “Newsreel of The Air.”

It was also an expensive proposition calling for greater participation by Time’s agency, BBDO, and the resources of a network if the program were to be immediate in its reporting. Smith knew that this was the kind of idea that would appeal to the young mavericks at CBS. But even CBS was apprehensive and like the magazine, needed reassurance that the idea would work.

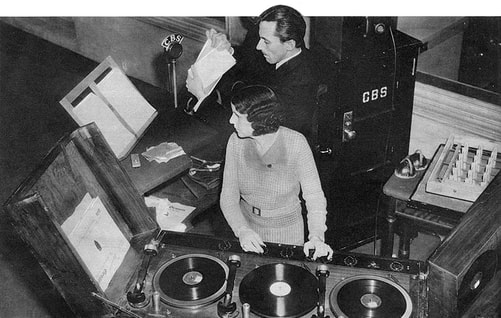

A meeting of network executives headed by Bill Paley and Henry Luce accompanied by Time editors was held at Roy Larsen’s home on February 6, 1931, to pass judgment on an audition broadcast of the new program - The March of Time - prepared for the group. When it was over no one became an immediate fan. Nevertheless, it was decided to proceed - with caution. It was determined that the program was on the right track by writing and presenting each segment in the concise style of the magazine with an authoritative narrator and that the actors chosen to portray major or incidental characters in each story be authentic in their speech or dialect. (3) CBS Music Director Howard Barlow was assigned the scoring and conducting duties for the program’s full studio orchestra and sound effects were given special attention for accuracy performed by Ora Nichols and her crew of assistants.

After much painstaking rehearsal and polishing, the first episode of The March of Time was broadcast on CBS during the eighth anniversary week of the magazine, on Friday, March 6, 1931 at 10:30 p.m. It led with dramatizations of the re-election of Chicago Mayor William (Big Bill) Thompson, the sale of The New York World to Scripps-Howard and its merger with The New York Evening Telegram, the transport of 774 French convicts to Devil’s Island, King Alfanso of Spain denying revolution, the return of King Carol of Romania, the auction of Russian royal artifacts in New York City and the musical closing of the 71st session of the U.S. House of Representatives. (4) It went off without a hitch.

Variety’s review of the premiere in its issue of March 11, 1931, was favorable: “First in a series sponsored by Time, the weekly mag. Object, as announced, is to re-enact, as clearly as radio will permit, scenes that occurred as new during the week. The manner of enacting these “memorable” scenes might make this program within a short period of time on of the most popular on the air. … Everything was highly effective, colorful and smartly presented.”

By July, 1931, CBS and Time felt enough confidence in the program to move it back to the heart of Friday nights at 8:30. It was located in that timeslot when it was first rated in the 1932-33 season and returned a 15.3 Crossley rating, good for 26th in the rankings opposite the hour-long Cities Service Concert on NBC starring the immensely popular Jessica Dragonette who scored a 20.2 season rating. The March of Time narrowed the soprano’s lead in the 1933-34 season with an 18.9 rating to Dragonette’s 19.6 and became CBS‘s top rated Friday night program of the season.

The increasingly popular March of Time was moved up 30 minutes on Friday nights to 9:00 p,m. and into a 21.5 rating for the 1934-35 season - a natural lead-in to the new movie-based Hollywood Hotel at 9:30. It was a combination that won the Friday night hour for CBS. The rating and its accompanying 17th place ranking for the season would be the highest ever achieved for The March of Time which soon became the victim of network, schedule and format jockeying.

From that top rated season, The March of Time of April 5, 1935, is posted. Narrated by Harry Von Zell, it reported on British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden’s meeting with Soviet Premier Josef Stalin, (plus a comment from the program’s “Benito Mussolini”); a bizarre test of how far blood can spurt recreated from the second murder trial of Stanford University executive David Lamson; the war of words between Martha Young and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt regarding Labor Secretary Frances Perkins appearance before the Charter Day Alumni Dinner at the University of California; the Supreme Court aftermath of the Scottsboro, Alabama trial of nine black youths accused of attacking a white girl, and a farewell performance tribute to Metropolitan Opera conductor Vincenzo Bellezza.

To cover such a wide range of voices needed in each broadcast, actors were either chosen from the program’s roster of ten first call performers or its standby pool of hundreds in New York City. Phil Adams, Ted de Corsia, Miriam Hopkinson, Ed Jerome, Jeanette Nolan, Bill Pringle, Frank Reddick, Jack Smart, Paul Stewart, Dwight Weist, were on The March of Time’s permanent staff in mid-1935 and each was paid a $150 weekly retainer.

By most any standards it can be judged that The March of Time during this period was objective, informative and entertaining, worthy of its four year ranking within Network Radio’s Top 20 programs. It was also during this period that Time’s Roy Larson was approached by young film producer Louis deRouchmont, to extend The March of Time into a continuing series of two-reel documentary films, each focused on a single subject and released to theaters at the rate of one a month. He projected the cost at $25,000 per episode to be recouped with a proceeds from theater rentals. With the success of the radio series, Larsen was an easy sell for de Rouchemont’s idea. (5) The movie series debuted on February 1, 1935 and extended until August, 1951. At its peak it was seen in over 8,000 theaters.

The booming signature voice of The March of Time films, (Cornelius) Westbrook Van Voorhis, also became the narrator of the radio series during the 1935-36 season. Van Voorhis’s commanding delivery announcing the series, (a style known in the trade as, “the voice of God”), belied the fact that he was barely into his early thirties. He became famous over the next 20 years by reminding radio listeners and movie goers that, “TIME…Marches On!”

The 1935-36 season also saw major change to The March of Time that nearly killed the show.

Time, CBS and the show’s sponsors of the period, Remington-Rand and Wrigley Gum, decided to convert the program from a weekly half-hour to a nightly quarter-hour, Monday through Friday strip at 10:30 p.m. The move, from late August, 1935, to September, 1936, was designed to make the program more immediate and concentrate on events of the day that they happened.

Variety’s review of August 28, 1935, pointed out its major flaw: “…The inaugural program serves as an example and object lesson of difficulties in the new setup. As a weekly program March of Time previously had seven days of front pages to glean. Now, only timely events occurring on the day of broadcast are available and Monday’s happenings were few. It was a dull late August wash day...”

It was also a ratings disaster. The new format cut The March of Time’s ratings 54%, from 20.5 to 9.5, and pushed its annual ranking from 17th to 36th. The quality of the program didn’t suffer - a production staff of 75 worked hard to assure that and these examples from May 7, 1936 and May 27, 1936 prove it. But Variety’s review proved spot-on and the public wasn’t ready for another nightly news program - particularly one that interfered with two popular 10:00 to 11:00 hours on NBC: Your Hit Parade on Wednesday and Bing Crosby‘s Kraft Music Hall on Thursday.

The March of Time reverted to its former 30-minute form on CBS Thursday nights at 10:30 for a final season beginning on October 15, 1936, but still had to contend with Crosby on NBC. Because the show was largely sustaining, it was also unrated. Electrolux appliances pick up its sponsorship for the 1937-38 season and moved it to Blue. But once there on Thursday night at 8:30 p.m. it found itself in the middle of the ratings fight between the second half of Rudy Vallee’s hour on NBC and the second half of Kate Smith’s hour on CBS. The result was another tumble for The March of Time’s rating, down to a 4.1 and 88th in the season’s rankings.

The ratings downslide was unfortunate because the program’s quality seemed to improve with age. The broadcast from October 28, 1937, which dealt with the mayoral race in New York City and the Soviet purges, display the program’s increased emphasis upon Howard Barlow’s elaborate scoring and Westbrook Van Voorhis’s dramatic narration. The final broadcast in this collection, January 6, 1938, begins with a survey of 1937’s Top Ten Movies, incorporates stories on sea piracy, Italy’s awards for large families and finishes with China’s scorched earth plans to destroy Shanghai in the wake of Japanese invasion.

The March of Time returned for the 1938-38 season on Blue at 9:30 p.m. on Friday. But nothing seemed to help the program’s ratings which finished its run on April 28, 1939, with a 5.2 average in 89th place. It sat out two seasons until Time brought it back on October 9, 1941, for another season on Blue at 9:30 on Friday nights. But even the outbreak of World War II couldn’t help the newsmagazine’s review of the week on radio. It’s 39-week average rating was 5.4 which put it in an embarrassing 119th place for the season.

Finally, broadcasting sense took hold at Time, Inc., and after a year off the air, The March of Time got a head start on the 1942-43 season on July 9th by opening on NBC at 10:30 Thursday night - following Rudy Vallee instead of opposite him. Two seasons of ratings success followed. VanVoorhis, Barlow and Company finished the 1942-43 season at their highest level since 1934-35, a 17.9 rating and 18th place. They followed in 1943-44 with a 16.0 rating in 22nd place. Both seasons ended with The March of Time finishing solidly in the middle of Friday's Top Ten Programs.

Meanwhile something was happening behind the scenes that spoiled it all. Time, Inc., bought 12½% of the Blue Network from its new owner, Ed Noble. (See The 1943-44 Season.) (6) It only seemed to make sense in the corporate boardroom that the company should show solidarity with its new network property and move The March of Time to the Blue Network. So, the program left NBC at 10:30 p.m. on Thursday, October 26th following Abbott & Costello’s Top Ten show and turned up seven days later on Blue at 10:30 following a 15-minute series of political talks and once again opposite Rudy Vallee on NBC.

The results were predictable. The March of Time finished the 1944-45 season and left the air with a 7.7 rating, tied for 103rd place with the mundane CBS sitcom, Those Websters.

It was never heard again. It deserved better.

(1) At its peak in 1979, Time, Incorporated, published Time, Life, Fortune, People, Sports Illustrated and Money magazines.

(2) Newsreels, (short films of current events), were produced for movie theaters until the 1960’s. They were introduced in the United States by Charles Pathe in 1910. Hearst’s Metrotone News followed in 1914, Paramount News in 1927, Fox Movietone News in 1928 and Universal News in 1929. The films were generally seven to ten minutes in length and distributed to client theaters twice per week.

(3) Orson Welles, Agnes Moorhead, Art Carney and Arlene Francis were among the first of many young actors who received talent checks from the program, but never any air credits.

(4) This recording is flawed as can be expected from one that’s over 85 years old. A good selection of March of Time broadcasts can be found at www.otrrlibrary.org

(5) Louis de Rochemont, (1899-1978), gained fame as a documentary film maker with The March of Time. He also won an Academy Award for 1944’s feature-length documentary The Fighting Lady. He produced the popular feature films Boomerang!, The House On 92nd Street, 13 Rue Madeline, The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone and Cinerama Holiday. He was succeeded as Producer of The March of Time in 1943 by his brother, Richard, who led the series until its conclusion in August, 1951.

(6) The company divested its holding in the Blue Network after a year of its purchase, but revived its interest in station holdings in the 1960’s. By 1965 Time-Life Broadcasting owned and then sold KLZ AM-FM-TV/Denver, KOGO AM-FM-TV/San Diego, WFBM AM-FM-TV/Indianapolis, WOnOD AM-FM-TV/Grand Rapids, Michigan and KERO(TV)/Bakersfield, California.

Copyright © 2018, Jim Ramsburg, Estero FL Email: [email protected]

This is the story of how a unique news program that scored six Top 50 seasons - two in the Top 20 - over a ten year run on three networks was nearly killed once, revived to new popularity, then permanently killed by corporate bungling. It's the story of The March of Time.

It began shortly after World War I when young Henry Luce and Briton Hadden were college pals in charge of the Yale Daily News. There they came up with the idea to create a weekly news magazine, (originally called Facts), which would present the top stories of each seven-day period in a concise, well-written style appealing to the tastes of the modern reader.

Their first edition of Time, appeared on newsstands during the first week of March, 1923. It sold 12,000 copies, mostly through the direct mail campaigns of their first hire, Roy E. Larsen, 23, who had built a reputation in college for turning The Harvard Advocate, an undergraduate magazine, into a surprisingly profitable publication. With Larsen fanning Time’s promotional flames, circulation doubled by the end of 1923 and hit 70,000 a week in 1924.

Larsen became Luce's junior partner when Hadden died suddenly in 1929. He was chiefly responsible for growing the company’s initial investment of $86,000 into a publishing empire valued at $1.69 Billion when he retired 56 years later at age 80. (1) He was also among the first to embrace other media for their promotional value to increase his magazines’ circulation. He was a willing listener when Fred Smith, Station Manager of WLW/Cincinnati paid him a visit in 1928 and proposed that Time join forces with the station to prepare weekly newscast scripts up to 15 minutes in length based on the magazine’s contents. Larsen obtained reluctant permission from a skeptical Luce and Time’s “Newsreel of The Air” began on WLW September 3, 1928. (2)

Other stations around the country which, like WLW, were shut out of news sources by the newspaper controlled wire services, asked to share in Time’s scripts. The magazine’s advertising agency, Batten, Barton, Durstine & Osborne was more than happy to distribute them, along with source credits for the magazine. The requests began to snowball and by September, 1929, the agency began to record the weekly scripts distribute the transcriptions to over 100 of America’s 600 stations.

Time’s circulation continued to grow and passed 150,000 a week in 1931 when WLW’s Smith approached Larsen with another idea. Radio news was still in its infancy and remote broadcasts of news events as they happened were rare. Smith proposed taking the radio program to a new level with dramatic recreations of current events and the reactions to them by actors impersonating the voices of the persons involved. The concept was entirely new, uniquely bold and, if treated properly, would truly result in a “Newsreel of The Air.”

It was also an expensive proposition calling for greater participation by Time’s agency, BBDO, and the resources of a network if the program were to be immediate in its reporting. Smith knew that this was the kind of idea that would appeal to the young mavericks at CBS. But even CBS was apprehensive and like the magazine, needed reassurance that the idea would work.

A meeting of network executives headed by Bill Paley and Henry Luce accompanied by Time editors was held at Roy Larsen’s home on February 6, 1931, to pass judgment on an audition broadcast of the new program - The March of Time - prepared for the group. When it was over no one became an immediate fan. Nevertheless, it was decided to proceed - with caution. It was determined that the program was on the right track by writing and presenting each segment in the concise style of the magazine with an authoritative narrator and that the actors chosen to portray major or incidental characters in each story be authentic in their speech or dialect. (3) CBS Music Director Howard Barlow was assigned the scoring and conducting duties for the program’s full studio orchestra and sound effects were given special attention for accuracy performed by Ora Nichols and her crew of assistants.

After much painstaking rehearsal and polishing, the first episode of The March of Time was broadcast on CBS during the eighth anniversary week of the magazine, on Friday, March 6, 1931 at 10:30 p.m. It led with dramatizations of the re-election of Chicago Mayor William (Big Bill) Thompson, the sale of The New York World to Scripps-Howard and its merger with The New York Evening Telegram, the transport of 774 French convicts to Devil’s Island, King Alfanso of Spain denying revolution, the return of King Carol of Romania, the auction of Russian royal artifacts in New York City and the musical closing of the 71st session of the U.S. House of Representatives. (4) It went off without a hitch.

Variety’s review of the premiere in its issue of March 11, 1931, was favorable: “First in a series sponsored by Time, the weekly mag. Object, as announced, is to re-enact, as clearly as radio will permit, scenes that occurred as new during the week. The manner of enacting these “memorable” scenes might make this program within a short period of time on of the most popular on the air. … Everything was highly effective, colorful and smartly presented.”

By July, 1931, CBS and Time felt enough confidence in the program to move it back to the heart of Friday nights at 8:30. It was located in that timeslot when it was first rated in the 1932-33 season and returned a 15.3 Crossley rating, good for 26th in the rankings opposite the hour-long Cities Service Concert on NBC starring the immensely popular Jessica Dragonette who scored a 20.2 season rating. The March of Time narrowed the soprano’s lead in the 1933-34 season with an 18.9 rating to Dragonette’s 19.6 and became CBS‘s top rated Friday night program of the season.

The increasingly popular March of Time was moved up 30 minutes on Friday nights to 9:00 p,m. and into a 21.5 rating for the 1934-35 season - a natural lead-in to the new movie-based Hollywood Hotel at 9:30. It was a combination that won the Friday night hour for CBS. The rating and its accompanying 17th place ranking for the season would be the highest ever achieved for The March of Time which soon became the victim of network, schedule and format jockeying.

From that top rated season, The March of Time of April 5, 1935, is posted. Narrated by Harry Von Zell, it reported on British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden’s meeting with Soviet Premier Josef Stalin, (plus a comment from the program’s “Benito Mussolini”); a bizarre test of how far blood can spurt recreated from the second murder trial of Stanford University executive David Lamson; the war of words between Martha Young and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt regarding Labor Secretary Frances Perkins appearance before the Charter Day Alumni Dinner at the University of California; the Supreme Court aftermath of the Scottsboro, Alabama trial of nine black youths accused of attacking a white girl, and a farewell performance tribute to Metropolitan Opera conductor Vincenzo Bellezza.

To cover such a wide range of voices needed in each broadcast, actors were either chosen from the program’s roster of ten first call performers or its standby pool of hundreds in New York City. Phil Adams, Ted de Corsia, Miriam Hopkinson, Ed Jerome, Jeanette Nolan, Bill Pringle, Frank Reddick, Jack Smart, Paul Stewart, Dwight Weist, were on The March of Time’s permanent staff in mid-1935 and each was paid a $150 weekly retainer.

By most any standards it can be judged that The March of Time during this period was objective, informative and entertaining, worthy of its four year ranking within Network Radio’s Top 20 programs. It was also during this period that Time’s Roy Larson was approached by young film producer Louis deRouchmont, to extend The March of Time into a continuing series of two-reel documentary films, each focused on a single subject and released to theaters at the rate of one a month. He projected the cost at $25,000 per episode to be recouped with a proceeds from theater rentals. With the success of the radio series, Larsen was an easy sell for de Rouchemont’s idea. (5) The movie series debuted on February 1, 1935 and extended until August, 1951. At its peak it was seen in over 8,000 theaters.

The booming signature voice of The March of Time films, (Cornelius) Westbrook Van Voorhis, also became the narrator of the radio series during the 1935-36 season. Van Voorhis’s commanding delivery announcing the series, (a style known in the trade as, “the voice of God”), belied the fact that he was barely into his early thirties. He became famous over the next 20 years by reminding radio listeners and movie goers that, “TIME…Marches On!”

The 1935-36 season also saw major change to The March of Time that nearly killed the show.

Time, CBS and the show’s sponsors of the period, Remington-Rand and Wrigley Gum, decided to convert the program from a weekly half-hour to a nightly quarter-hour, Monday through Friday strip at 10:30 p.m. The move, from late August, 1935, to September, 1936, was designed to make the program more immediate and concentrate on events of the day that they happened.

Variety’s review of August 28, 1935, pointed out its major flaw: “…The inaugural program serves as an example and object lesson of difficulties in the new setup. As a weekly program March of Time previously had seven days of front pages to glean. Now, only timely events occurring on the day of broadcast are available and Monday’s happenings were few. It was a dull late August wash day...”

It was also a ratings disaster. The new format cut The March of Time’s ratings 54%, from 20.5 to 9.5, and pushed its annual ranking from 17th to 36th. The quality of the program didn’t suffer - a production staff of 75 worked hard to assure that and these examples from May 7, 1936 and May 27, 1936 prove it. But Variety’s review proved spot-on and the public wasn’t ready for another nightly news program - particularly one that interfered with two popular 10:00 to 11:00 hours on NBC: Your Hit Parade on Wednesday and Bing Crosby‘s Kraft Music Hall on Thursday.

The March of Time reverted to its former 30-minute form on CBS Thursday nights at 10:30 for a final season beginning on October 15, 1936, but still had to contend with Crosby on NBC. Because the show was largely sustaining, it was also unrated. Electrolux appliances pick up its sponsorship for the 1937-38 season and moved it to Blue. But once there on Thursday night at 8:30 p.m. it found itself in the middle of the ratings fight between the second half of Rudy Vallee’s hour on NBC and the second half of Kate Smith’s hour on CBS. The result was another tumble for The March of Time’s rating, down to a 4.1 and 88th in the season’s rankings.

The ratings downslide was unfortunate because the program’s quality seemed to improve with age. The broadcast from October 28, 1937, which dealt with the mayoral race in New York City and the Soviet purges, display the program’s increased emphasis upon Howard Barlow’s elaborate scoring and Westbrook Van Voorhis’s dramatic narration. The final broadcast in this collection, January 6, 1938, begins with a survey of 1937’s Top Ten Movies, incorporates stories on sea piracy, Italy’s awards for large families and finishes with China’s scorched earth plans to destroy Shanghai in the wake of Japanese invasion.

The March of Time returned for the 1938-38 season on Blue at 9:30 p.m. on Friday. But nothing seemed to help the program’s ratings which finished its run on April 28, 1939, with a 5.2 average in 89th place. It sat out two seasons until Time brought it back on October 9, 1941, for another season on Blue at 9:30 on Friday nights. But even the outbreak of World War II couldn’t help the newsmagazine’s review of the week on radio. It’s 39-week average rating was 5.4 which put it in an embarrassing 119th place for the season.

Finally, broadcasting sense took hold at Time, Inc., and after a year off the air, The March of Time got a head start on the 1942-43 season on July 9th by opening on NBC at 10:30 Thursday night - following Rudy Vallee instead of opposite him. Two seasons of ratings success followed. VanVoorhis, Barlow and Company finished the 1942-43 season at their highest level since 1934-35, a 17.9 rating and 18th place. They followed in 1943-44 with a 16.0 rating in 22nd place. Both seasons ended with The March of Time finishing solidly in the middle of Friday's Top Ten Programs.

Meanwhile something was happening behind the scenes that spoiled it all. Time, Inc., bought 12½% of the Blue Network from its new owner, Ed Noble. (See The 1943-44 Season.) (6) It only seemed to make sense in the corporate boardroom that the company should show solidarity with its new network property and move The March of Time to the Blue Network. So, the program left NBC at 10:30 p.m. on Thursday, October 26th following Abbott & Costello’s Top Ten show and turned up seven days later on Blue at 10:30 following a 15-minute series of political talks and once again opposite Rudy Vallee on NBC.

The results were predictable. The March of Time finished the 1944-45 season and left the air with a 7.7 rating, tied for 103rd place with the mundane CBS sitcom, Those Websters.

It was never heard again. It deserved better.

(1) At its peak in 1979, Time, Incorporated, published Time, Life, Fortune, People, Sports Illustrated and Money magazines.

(2) Newsreels, (short films of current events), were produced for movie theaters until the 1960’s. They were introduced in the United States by Charles Pathe in 1910. Hearst’s Metrotone News followed in 1914, Paramount News in 1927, Fox Movietone News in 1928 and Universal News in 1929. The films were generally seven to ten minutes in length and distributed to client theaters twice per week.

(3) Orson Welles, Agnes Moorhead, Art Carney and Arlene Francis were among the first of many young actors who received talent checks from the program, but never any air credits.

(4) This recording is flawed as can be expected from one that’s over 85 years old. A good selection of March of Time broadcasts can be found at www.otrrlibrary.org

(5) Louis de Rochemont, (1899-1978), gained fame as a documentary film maker with The March of Time. He also won an Academy Award for 1944’s feature-length documentary The Fighting Lady. He produced the popular feature films Boomerang!, The House On 92nd Street, 13 Rue Madeline, The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone and Cinerama Holiday. He was succeeded as Producer of The March of Time in 1943 by his brother, Richard, who led the series until its conclusion in August, 1951.

(6) The company divested its holding in the Blue Network after a year of its purchase, but revived its interest in station holdings in the 1960’s. By 1965 Time-Life Broadcasting owned and then sold KLZ AM-FM-TV/Denver, KOGO AM-FM-TV/San Diego, WFBM AM-FM-TV/Indianapolis, WOnOD AM-FM-TV/Grand Rapids, Michigan and KERO(TV)/Bakersfield, California.

Copyright © 2018, Jim Ramsburg, Estero FL Email: [email protected]

| march_of_time__3-06-31.mp3 | |

| File Size: | 25073 kb |

| File Type: | mp3 |

| march_of_time__4-05-35.mp3 | |

| File Size: | 28602 kb |

| File Type: | mp3 |

| march_of_time__5-07-36.mp3 | |

| File Size: | 14393 kb |

| File Type: | mp3 |

| march_of_time__5-27-36.mp3 | |

| File Size: | 14878 kb |

| File Type: | mp3 |

| march_of_time__10-28-37.mp3 | |

| File Size: | 28361 kb |

| File Type: | mp3 |

| march_of_time__10-28-37.mp3 | |

| File Size: | 28361 kb |

| File Type: | mp3 |

| march_of_time__1-06-38.mp3 | |

| File Size: | 28445 kb |

| File Type: | mp3 |