AND ALL THE SHIPS AT SEA…

“Good evening, Mr. & Mrs. North and South America and all the ships at sea…let’s go to press !”

Was Walter Winchell a showman posing as a journalist or a journalist posing as a showman? Whether his story is told in Neal Gabler’s excellent Winchell: Gossip, Power And The Culture of Celebrity, Lyle Stuart’s biting Secret Life of Walter Winchell or Winchell - His Life & Times written by the columnist’s longtime ghostwriter, Herman Klurfeld, Winchell remains an enigma who put “The Column” and “The Broadcast” above everything and everyone else in his life.

As a result, his column was once carried in over 2,000 newspapers and his Sunday night Jergens Journal was the most popular 15-minute program of Network Radio’s Golden Age. Yet, his daughter Walda was the only mourner at his funeral in 1972.

Born into poverty on April 7,1897, in New York City, Walter Winschel left school at 13 with his lifelong pal George Jessel to join the Gus Edwards production Song Revue as part of the show’s Newsboys sextet. (1) He remained with the touring group of juveniles as a performer and stage assistant until 1917 when he and 17 year old Rita Greene debuted as the song and dance team, Winchell & Greene. His name change from Winschel to Winchell for marquee purposes became permanent.

The act remained busy with bookings until Winchell joined the U.S. Navy in the summer of 1918. When he returned from service six months later they hit the road again and after landing two-years’ of bookings from the Keith and Pantages circuits at $250 a week, ($3,400 in today’s money), they were married on August 11, 1919. It was little more than a marriage of convenience - the couple separated in 1922 and divorced in 1928. (2)

Winchell’s career as a journalist - without portfolio or pay - began in February, 1920, when the first of his columns, Stage Whispers by The Busybody, appeared in Billboard. That led to Daily Newssense, a backstage sheet of vaudeville gossip.

He sent samples of Newssense to the Vaudeville News, an eight-page house organ of Edward Albee’s National Vaudeville Artists, a 12,000 member “union” controlled by theater owners and managers. His submissions soon became regular features titled Pantages Paragraphs and Merciless Truths.

Finally, in November, 1921, he was hired by the Vaudeville News for $25 a week, ($330 in today’s money). The 24 year old ex-hoofer had become a professional columnist Nevertheless, he had to supplement his income by selling ads in the trade paper.

Winchell’s big break came three years later when he was hired as a columnist and drama critic for Bernarr Macfadden’s New York Evening Graphic for $75 a week. It was a cut in pay for Winchell who had become a successful advertising salesman for the Vaudeville News, but it was his opportunity to write for a New York daily newspaper and that was more important than money.

The tabloid Graphic, funded by profits from Macfadden’s successful magazines, Physical Culture and True Story, had gained the dubious reputation as the epitome of yellow journalism. Your Broadway And Mine by Walter Winchell, full of gossip and slang, debuted on September 20, 1924, and fit right in. Variety founder-publisher Sime Silverman and nightclub hostess Texas Guinan became Winchell's mentors and the main sources of tips for his column as he developed new informants among the city‘s scores of press agents. Winchell became the star of the paper and his column was a “must read“ for gossip hungry New Yorkers.

Winchell’s growing fame led to his first appearance on radio in the fall of 1928 - a Will Rogers “campaign” broadcast promoting his mock presidential candidacy. A few months later in January, 1929, the columnist “conducted a tour of Broadway” on the 42 station NBC network and followed that with appearances on Rudy Vallee’s Thursday night Fleischmann Yeast Hour on NBC at $250 each, ($3400 in today‘s money). Vallee, a shrewd judge of talent, encouraged Winchell to pursue a broadcasting career. (3)

Despite his importance to the paper, internal politics caused the Graphic to fire Winchell in May, 1929. (4) William Randolph Hearst immediately signed the columnist for his morning tabloid, the New York Daily Mirror, luring him with an undisclosed signing bonus, $500 a week and 50% of the column's gross syndication revenues distributed by Hearst‘s King Features. With much fanfare Winchell's first column appeared in the Mirror on June 10, 1929

The Great Depression was looming but nothing would stop the growth of Winchell’s career and wealth. The columnist had himself become a colorful character, roaming Broadway after dark, befriending politicians, show people and gangsters, holding court for press agents and their clients every night in the Cub Room of the Stork Club and racing around until dawn in his police radio equipped car. Before long, he established working and living quarters at the St. Moritz Hotel and seldom went near the Mirror's offices.

Much to the chagrin of the journalism establishment, Winchell’s columns on page ten of the Mirror stringing together unrelated items of sensationalized news and gossip separated by ellipses and flavored by his metaphoric slang became wildly popular.

Terms like ankle, (to leave), a blessed event or storked, (having a baby), Chicagorilla, (a Chicago hoodlum), debutramp, (a girl with loose morals), giggly water, (liquor), Hard Times Square, (Depression-era Broadway), infanticipating, (expecting a baby), Joosh, (Jewish), Lohengrinned or middle-aisling, (getting married), Main Stem, (Broadway), moom picher, (a movie), phewd, (a smelly feud), phfft!, (a breakup), revusical, (a musical), radiodor, (a bad radio show), pash, (passion), Reno-vated, (divorced), shafts, (legs) and vomics, (dialect comedians), became models for his many imitators.

Marlen Pew, editor of the journalism trade magazine Editor & Publisher, wrote of the Winchell-led breed, “In fact, much of the stuff is faked or guessed. Other matter is dirt no respectable writer would put on paper. It is a dirty business.” Nevertheless, syndication money for Winchell’s column poured in from “respectable” papers all across the country.

CBS owned WABC/New York was first to capitalize on Winchell’s notoriety on Monday, May 12, 1930, with a weekly 15 minute gossip chatterfest sponsored by Saks Department Store at 7:45 p.m. The show was called Before Dinner, but then - possibly looking at the clock - it was renamed Saks Broadway With Walter Winchell. As quoted in the Gabler biography, he opened his first broadcast with, “I’m the Peek’s Blab Boy who turns Broadway’s dirt and mud into gold.” Saks cancelled the show in August but by that time Winchell had filmed his first Warner Brothers/Vitaphone short, The Bard of Broadway, and he was hotter than ever.

Hearst recognized his importance to newspaper circulation and gave him a new five year contract in September worth an estimated $121,000 per year. At mid-month he began a new Tuesday night radio series for Wise Shoe Company on WABC worth another $1,000 a week. Adding to his bank account in January, 1931, he emceed a stage show featuring Harry Richman and Lillian Roth at New York’s Palace Theater that paid him $3,500 for the week’s work. ($54,880 in today’s money). As he explained, “You can take the boy out of vaudeville but you can’t take vaudeville out of the boy.”

Winchell segued into his third WABC show on September 15, 1931, The quarter hour Tuesday night series for La Gerardine Hair Wave Cream for women was similar to the Wise program. Winchell's gossipy items were sandwiched between performances by his guest stars who, over the first month, included Kate Smith, Cab Calloway, Morton Downey and the Mills Brothers. Winchell also became friendly with Ben Bernie whose band followed the La Gerardine program on WABC and that led to good natured jibes between the two. Their paths would cross many times again.

Winchell’s fast paced 15 minute local variety show became popular with listeners - and one listener in particular: American Tobacco’s CEO, George Washington Hill. Hill was scouting for a new host for his hour long Lucky Strike Dance Orchestra broadcasts on NBC three nights a week.

As he proved in the case of Jack Benny in 1944, whatever George Washington Hill wanted, George Washington Hill got He offered La Gerardine an incredible $35,000, ($540,500 in today‘s money), just to let Winchell appear on the Lucky Strike show for a month, while his Lord & Thomas advertising agency sampled listener reaction..

On Tuesday, November 3, 1931, Winchell did the La Gerardine show with Ruth Etting on WABC at 8:45 for 15 minutes, then raced over to NBC’s studios for his first Lucky Strike Dance Orchestra broadcast featuring Wayne King’s band at 10:00. That, plus the Thursday and Saturday night Lucky Strike shows, became his routine for the next seven weeks as he “auditioned” for George Washington Hill and scrambled to find his successor to host the La Gerardine show.

Winchell left the WABC program on December 15th and a month later the replacement he recruited - a 30 year old sportswriter turned Broadway columnist from the Evening Graphic - took over. As a result, the La Gerardine show of January 12, 1932, was the beginning of Ed Sullivan‘s 39 year radio and television career.

Winchell’s contract for the Lucky Strike broadcasts called for $3,500 a week - among the top salaries in Network Radio. Coupled with his Hearst column and syndication income he was making over $6,000 a week, ($102.800 in today‘s money). By the spring of 1932, Lucky Strike had 45,000 billboards across the country and full page magazine ads featuring Winchell. Whether listeners liked him or not, Lucky Strike had made him a national figure.

And not everyone liked Winchell. He had the protection of his friend, gangster Owney Madden, but he claimed that death threats had become routine in 1932, particularly after Vincent Mad Dog Coll was gunned down by Madden’s henchmen in February. He blamed the overwhelming pressure of impending doom to cause his collapse after the Lucky Strike broadcast of April 16th.

Winchell left for California to recuperate and while there agreed to film Okay, America!, (his Lucky Strike catch-phrase), for $50,000 at Universal. A month later he reneged on the handshake deal, held out for $100,000 and returned to New York. He resumed his newspaper column in the Mirror on June 1st and the Lucky Strike broadcasts on June 16th although comedian Walter O’Keefe had taken over as host of the program during his absence. Two months later Winchell suffered another questionable collapse and left the program permanently. (5)

How sick was he? During September Winchell agreed to a contract with Universal to appear in 13 filmed shorts - although the number turned out to be only two - 1933’s I Know Everybody & Everybody’s Racket and Beauty On Broadway. He also wrote the story for the movie Broadway Thru A Keyhole based on Al Jolson’s courtship of dancer-actress Ruby Keeler, which earned him a reported $30,000 and a highly reported punch in the nose from Jolson.

During his “illness” Winchell also produced his daily column and negotiated what turned out to be his radio contract of a lifetime with the Andrew Jergens Company for a 15 minute newscast every Sunday night on the Blue Network.

He hit the air running with the Jergens Journal on Sunday, December 4, 1932, at 9:30 p.m, scoring an 8.7 Crossley rating for the month. His average rating for the season was 11.6, edging out American Album of Familiar Music’s 10.0 on NBC, his only rated competition in the time period. Winchell’s 44th place finish among all programs was his first of 21 consecutive Top 50 finishes - a feat matched only by Jack Benny.

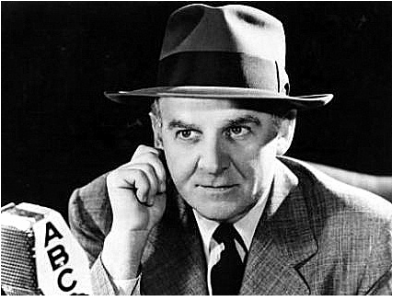

Poised in shirtsleeves, loosened tie, belt and fly, and wearing his trademark fedora, Winchell attempted to launch every Jergens Journal with a “Flash!” news item - the more sensational the better. That was followed by a staccato-delivered barrage of news, gossip and human interest items, each begun with Winchell barking out its dateline which seemed to elevate the most obscure divorce notice to the level of world importance. Everything but Winchell’s opinion pieces were breathlessly delivered at breakneck speed and separated by the audio version of his columns’ ellipses, brief bursts of telegraph key rattle.

Winchell considered the most important part of every broadcast to be its final item, “The Lasty.” Delivered every week with “Lotions of love…” the cleverly written human interest or opinion piece was the “kicker” to each show. Winchell and his longtime ghostwriter, Herman Klurfeld, would consider up to a dozen or more lines before settling on each week‘s “Lasty”. From its opening to its close, the Jergens Journal was unlike anything else on the air - and that’s exactly what Winchell wanted.

Winchell was outside the boundaries of 1933’s Biltmore Agreement which established the Press Radio Bureau and its stringent limits on radio news because he was considered a “commentator" not a “newscaster". As a result, he had virtually no network competition for breaking news on weekends during the much of the 1930’s.

He also began a string of 21 straight seasons of Top Ten finishes on Sunday night - another accomplishment he shared with Benny. Nevertheless, Winchell had a seven year battle for 9:30 Sunday time period leadership with American Album of Familiar Music, losing two of the first three before taking command

An unabashed fan of J. Edgar Hoover’s gang-busting FBI and the populist politics of the newly elected President Franklin Roosevelt in both his columns and broadcasts, Winchell turned his attention from the trivial affairs of Broadway to national concerns. (6) Hoover responded with friendship and influence, both of which proved useful when the “Story of The Decade” - to that time - broke in September, 1933.

The tracking and arrest of Bruno Hauptmann for the kidnapping and murder of the Lindbergh baby became Winchell’s obsession. He made it his story, receiving both plaudits and scorn for his investigative work as the authorities closed in on Hauptmann. Hoover later publicly praised “a certain well-known columnist” for sacrificing an international scoop by not divulging confidential information that led to Hauptmann’s arrest. Jergens rewarded its “certain well-known columnist” with a new contract in May, 1934 - 39 weeks at $2,000 a broadcast.

When Hauptmann’s trial began on January 3, 1935, Jergens had upped Winchell’s salary to $2,500 a week and agreed to indemnify him against any damages awarded for libel, slander, invasion of privacy or copyright infringement. He sat smiling in a front row seat while all of the prospective jurors were asked if they had ever read a Walter Winchell column or heard any of his radio broadcasts. It was the kind of publicity that money couldn’t buy and Winchell’s ratings jumped nearly 30% during the trial,

Once the trial was over Winchell’s ratings sank back into the single digits in the 1935-36 season. Meanwhile, his old pal from WABC, Ben Bernie, was having his own problems. His new sponsor, American Can Company, moved The Old Maestro and his band from their three highly rated seasons on NBC to the Blue Network and brought about a 47% loss of audience.

Winchell and Bernie got together and created Network Radio’s first famous “feud” - cross-promoting each other with insults on their programs. It never reached the proportion of the Jack Benny/Fred Allen “feud,” but did result in two 1937 20th Century Fox films starring the pair as themselves: August’s Wake Up & Live and Love & Hisses in December. To promote the two movies, Winchell starred in Lux Radio Theater’s adaptation of The Front Page in June.

The notoriety of the two films got Bernie a new show on CBS with double digit ratings and helped solidify the Jergens Journal as a Top 20 show for three consecutive seasons through 1938-39 and pushed Winchell‘s weekly salary from his grateful sponsor up to $5,000.

Winchell made news on his own in August, 1939, by ending the 21 month manhunt for murderer Louis Lepke Buchalter who surrendered himself to the columnist, “The one person I can trust.” Winchell turned the killer over to J. Edgar Hoover but turned down the $50,000 reward offered for the fugitive’s capture, calling it his “gift to the people.”

Two other factors, however, played a greater role in Winchell’s pending success of huge proportions. His broadcasts had been evolving since the Hauptmann trial to more hard news and less trivial gossip. Winchell was a hawk - known in the prewar days as an “Interventionist”- who continually warned his listeners of the dangers if America wasn’t prepared to defend itself against the rise of fascism. The outbreak of war in Europe in late 1939 pushed his ratings up 38% and into the 20’s.

Of secondary importance, his Sunday night program was moved back from 9:30 to 9:00 p.m. ET in 1939. Historically, most of the Annual Top Ten programs started on the hour, not the half-hour. True to that form, Winchell scored his first of eight consecutive seasons in the Annual Top Ten in 1939-40. The program remained at 9:00 for 15 years, registering an overall total of twelve Top Ten finishes. (7)

He broke into the twenties in 1940-41 with a season average of 24.1. Four episodes of the Jergens Journal from the 1940’s are posted: May 18, 1941, February 25, 1945, April 22, 1945 and May 6, 1945. Listeners will pardon the poor audio quality but the recordings provide examples of the hectic pace Winchell set. By comparison, conversationally paced newscaster Lowell Thomas registered a season average of 14.2, H.V. Kaltenborn an 11.6 and Gabriel Heatter a 7.4. Then came Pearl Harbor.

Winchell’s Sunday night broadcast of December 7, 1941, fell within a Hooper survey week. The saber-rattling columnist suddenly became the prophet patriot and scored his highest single broadcast rating to date - a 29.9. (The poor recording of the broadcast is also posted below.) His January and February ratings climbed even higher to 33.1 - territory normally occupied by only the most popular variety shows. Not even the return of Fred Allen to a CBS variety hour opposite Winchell in mid-March could slow his ratings momentum. At 26.0, his 1941-42 average was the highest of his 21 consecutive Top 50 seasons.

After much pleading for active war duty to silence his critics, Winchell, who was a 45 year old Lieutenant Commander in the U.S. Navy Reserve, was called to service in late December, 1942. His assignment was simply a fact-finding mission to Brazil for the State Department, but the month in South America was enough to give him bragging rights as a uniformed veteran. The month away from his program didn’t harm the Jergens Journal’s ratings - just the opposite. Winchell’s numbers increased by approximately ten percent when he returned to the air in February.

The Jergens Journal was easily the most enduring and highest rated program ever originated by the Blue Network, peaking at Number Four as World War II neared its end in 1944-45, the only season when it was also Sunday’s most popular program, edging out perennial leaders Edgar Bergen and Jack Benny. (8)

After a down season in 1947-48 when the Jergens Journal slipped to 30th in the Annual Top 50 with nearly a 20% loss of audience, Winchell bounced back into the Top Ten in 1948-49 with almost a 30% gain and leading all programs in the February, March and June monthly ratings - the most monthly wins an ABC program would ever earn. (See The Monthlies on this site.)

Nevertheless, after a successful 16 year association, Jergens Lotion and Walter Winchell parted company in December, 1948, ending one of the longest sponsor-program relationships in prime time radio.

The columnist - reported to be another target of the CBS talent raid - became radio’s first “Thousand Dollar A Minute” star when he signed a widely publicized 90 week, $1.35 Million contract with Kaiser-Frazer automobiles after Jergens dropped out.

Winchell’s first broadcast for the auto maker in January, 1949, scored a 29.7 Hooperating but Kaiser-Frazer saw no significant sales results from the programs and opted out of the lavish contract after 26 weeks, just as Winchell was coming off his second Top Five season - a season that was punctuated with the death of an “enemy”...

Winchell was a strong proponent of the late FDR, but wary of the policies of President Harry Truman which he considered weak. In particular, he raged against the anti-Zionist stance of the country’s first Secretary of Defense, James Forrestal, a wealthy Republican. Winchell joined forces with Drew Pearson, another columnist/commentator foe of Forrestal, and unleashed non-stop attacks on the secretary, contributing to his forced resignation from Truman’s administration and letting up only when the hospitalized former cabinet member jumped to his death from the 16th floor of the Bethesda Naval Center on May 22, 1949. Two days later both Winchell and Pearson were denounced in Congress for contributing to Forrestal’s suicide with their relentless personal attacks.

Winchell seemed to overlook Forrestal’s early warnings of the menace Communism posed to postwar America - the same stance he took in his columns and broadcasts since before World War II. When war broke out in Korea 13 months after Forrestal’s death, Winchell turned his attacks to President Truman, especially after the firing of General Douglas MacArthur from his U.N. Korean command post in April, 1951. Winchell’s rebukes of Truman were so strong that many of his left-wing allies began to question his loyalties to the Democrats that were forged in the early days of the New Deal.

Listener loyalty was another question. Now under the sponsorship of William Warner Company’s Richard Hudnut Cosmetics, Winchell’s 21.7 average rating in 1948-49 sank almost 25% to 16.3 in 1949-50. But during a season when television gobbled up radio audiences by the millions and the average Top 50 Network Radio program lost 30% of its ratings, Winchell’s loss of some five million listeners every week was considered tolerable.

Hudnut and ABC which were both trying to talk their reluctant 53 year old star into simulcasting his Sunday night program on ABC’s fledgling television network. But Winchell didn’t want to be tied down to a New York television studio every week - Miami Beach had become his second home and playground in the winter. He also feared that he’d be competing against his own radio show which was still Number Six in the Annual Top Ten and second only to Jack Benny on Sunday nights.

In February, 1950, Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy claimed to have a list of 205 Communists who had infiltrated the State Department. It was the kind of material that Winchell had been seeking to substantiate his fears and warnings, but had been unable to find. Winchell met with McCarthy for two hours at the Stork Club during the summer and solidified their friendship of purpose and convenience. McCarthy and his subordinate, Roy Cohn, both knew how to push Winchell’s buttons and enlist him as an ally.

Winchell proudly proclaimed himself - like McCarthy - a “crusading commie fighter,” and began to fling innuendo-laden accusations with abandon in his columns and broadcasts. Newspapers began to severely edit or drop his syndicated columns altogether. His list of formidable critics and enemies grew to include leaders of both political parties, the NAACP and most every other influential syndicated columnist. Winchell found himself in a constant state of self-created public and private battles. But he considered himself to be a good soldier in Tailgunner Joe’s army fighting Communism and he was proud of it!

Winchell’s loss of audience continued to mirror Network Radio’s nighttime declines in 1950-51. His season rating of 12.4 was the lowest since 1935-36, yet enough to remain seventh in the Annual Top Ten and fourth on Sundays behind Jack Benny, Edgar Bergen and Amos & Andy. When the 1951-52 season began, ABC relented on its insistence that Winchell simulcast his Sunday night radio show, gave him a lifetime “consultancy” contract worth $1,000 a week and upped his pay to $8,000 per broadcast. In addition, Warner-Hudnut gave him 10,000 shares of company stock.

Winchell had made many enemies over the years - some of them sued him, others just feared him and his competitors resented him. Black chanteuse Josephine Baker tried got even with him for criticizing her denouncing American citizenship in 1936 to become a citizen of France. On her return to New York in October, 1951, she inflated an alleged case of discrimination at the Stork Club into headlines, contending that the incident, (very poor service), happened in Winchell’s presence and with his tacit approval, although he and witnesses claimed that he had left the nightclub earlier.

New York City officials found no case for discrimination, but Baker pursued it with a $400,000 defamation suit against Winchell and took her cause to Barry Gray’s late night interview show on WMCA/New York. Playing David to Winchell’s Goliath, Gray eagerly provided a microphone for Winchell’s enemies. By now that list included Ed Sullivan, who proclaimed, “I despise Walter Winchell because he symbolizes to me evil and treacherous things in the American set-up.” (Sullivan apparently forgot that the man he despised gave him his start in broadcasting.)

With the momentum of local New York columnists and commentators ganging up on Winchell with what they considered to be well deserved comeuppance, the New York Post began a unflattering 24-part series on Winchell’s life and career on January 7, 1952.

Less than three weeks later, on January 27th, Winchell closed his broadcast by claiming that his doctors had ordered him to take a month’s rest from, “all professional activities.” The Post suspended its series while he recuperated.

He returned to the air on March 9th, The Post series resumed on March 10th and Winchell promptly suffered a relapse in the midst of his twelfth and last Top Ten season, leaving the air before his March 16th broadcast. Winchell’s broadcasts were covered following his departure by Erwin Canham and Taylor Grant before Drew Pearson took over for the rest of the season in April. Despite his prolonged absences, Winchell’s 9.2 rating clung to ninth place in the Annual Top Ten and his show was still the fourth most popular on Sunday nights.

Nevertheless, Hudnut Cosmetics had enough of their star’s tantrums and traumas, cancelling its $500,000 annual sponsorship contract after three turbulent seasons.

Winchell returned to the air on October 5, 1953, seemingly refreshed after his six month leave of absence with a new sponsor, Gruen Watches. The Gruen contract called for an ABC-TV performance of his radio script on Sundays at 6:45 p.m. ET and his regular radio show at 9:00.

Two months later the New York Post filed a $1.5 Million libel suit against him, ABC, Hearst Newspapers, King Features and Gruen. It was the culmination of the eleven month feud ignited by The Post’s series that was highly critical of Winchell’s methods and ethics. In angry response, Winchell accused The Post, its publishers and editors of Communist leanings referring to the rival tabloid as, “That pinko-stinko sheet,” “The New York Pravda,” and “The New York Com-post.” Winchell’s continued smears against the paper and its editor James Wechsler, ("that former Commie”), in his newspaper columns and radio commentaries, led The Post to take their fight into court. Winchell promptly countersued for $2.0 Million and a lengthy, costly two year court battle began.

As Network Radio’s Golden Age came to a close, Winchell’s fear that his television show would cut into his radio popularity came to pass. His radio ratings plunged 40% over the 1952.-53 season. His Top Ten ranking of four consecutive seasons dropped to a tie for 36th place. He still remained in Sunday’s Top Ten but tied in his timeslot with the prestigious Hallmark Playhouse on CBS which became the Hallmark Hall of Fame at mid-season.

Winchell’s Sunday night program became a simulcast in September, 1953, but Gruen wanted to distance itself from The Post lawsuit and cancelled its sponsorship in December. His television and radio ratings were dismal and hardly worth the $520,000 that ABC was paying him.

The Post won its lawsuit two years later - settling for $30,000 in court costs and a retraction/apology from Winchell. The settlement was paid by ABC and Hearst. But the obstinate Winchell refused to say a word about the verdict. An ABC staff announcer was assigned read the apology on his broadcast of March 16, 1955..

Winchell’s penalty came three months later - the loss of his high paying ABC contract, ending his 23 year run on the network. He bid goodbye to his ABC audience on June 26, 1955, and was replaced the following Sunday - July 3, 1955 - by the network’s promising young newscaster, 36 year old Paul Harvey.

Winchell moved on to Mutual for the next two years. By that time it was open season on the columnist. Burt Lancaster’s scathing portrayal of the loathsome J.J. Hunsecker - an obvious caricature of Winchell in The Sweet Smell of Success - hit the screens shortly after Winchell left Network Radio. His last broadcast was on March 3,1957.

Six years later, on October 15, 1963, the New York Daily Mirror folded after a lengthy strike and Winchell was moved to Hearst‘s afternoon Journal-American. The paper cut his column back to three times a week and his syndication income dwindled to a fraction of its former figures. Hearst finally terminated its 38 year association with Winchell on November 30, 1967, and the once loudest voice in American journalism was silenced.

“…and so, with lotions of love, this is your New York correspondent Walter Winchell who knows that Broadway is a mountain…tough sledding on the way up and a toboggan on the way down.”

(1) Winchell would often refer to himself on his Sunday night broadcasts as “Mrs. Winchell’s Newsboy.”

(2) Winchell moved in with June Magee on May 11, 1923. The couple remained common-law man and wife until her death in February, 1970. They adopted adopted a baby daughter, Gloria, in October 1923. The child died at age nine from pneumonia. A daughter Eileen Joan (Walda) was born to the couple on March 21,1927, and son, Walter, Jr., born July 26, 1935. Although the couple maintained the pretense of wedlock, they lived apart most of the time and Winchell openly kept a string of girlfriends and mistresses.

(3) Winchell betrayed Vallee in February, 1939, by planting a front page story in the Miami Herald that the popular crooner had “slugged” a busboy backstage during an engagement at the Royal Palms nightclub. Vallee was exonerated but Winchell didn’t retract his story.

(4) The Graphic went bankrupt and ceased publication on July 7, 1932.

(5) Walter O’Keefe remained with the Lucky Strike Dance Hour and returned Top Ten Crossley ratings for the Tuesday and Saturday editions of the program until it left the air in April, 1933.

(6) Roosevelt summoned Winchell to the White House shortly after his inauguration to acknowledge the columnist’s support and assure his continued loyalty. The President used their mutual friend, Democratic National Committee counsel Ernest Cuneo, as a go-between for occasional scoops and more frequently, political points he wished Winchell to push.

(7) In 13 of C.E. Hooper’s 30 surveyed cities, Winchell was broadcast on the local NBC station.

(8) Winchell’s broadcasts were heard twice every Sunday on the West Coast from December 2, 1945, to December 25, 1949. The Blue/ABC affiliates carried the first feed at 6:00 p.m. PT and the Don Lee Network carried the second feed at 8:30.

Copyright © 2015 Jim Ramsburg, Estero FL Email: [email protected]

“Good evening, Mr. & Mrs. North and South America and all the ships at sea…let’s go to press !”

Was Walter Winchell a showman posing as a journalist or a journalist posing as a showman? Whether his story is told in Neal Gabler’s excellent Winchell: Gossip, Power And The Culture of Celebrity, Lyle Stuart’s biting Secret Life of Walter Winchell or Winchell - His Life & Times written by the columnist’s longtime ghostwriter, Herman Klurfeld, Winchell remains an enigma who put “The Column” and “The Broadcast” above everything and everyone else in his life.

As a result, his column was once carried in over 2,000 newspapers and his Sunday night Jergens Journal was the most popular 15-minute program of Network Radio’s Golden Age. Yet, his daughter Walda was the only mourner at his funeral in 1972.

Born into poverty on April 7,1897, in New York City, Walter Winschel left school at 13 with his lifelong pal George Jessel to join the Gus Edwards production Song Revue as part of the show’s Newsboys sextet. (1) He remained with the touring group of juveniles as a performer and stage assistant until 1917 when he and 17 year old Rita Greene debuted as the song and dance team, Winchell & Greene. His name change from Winschel to Winchell for marquee purposes became permanent.

The act remained busy with bookings until Winchell joined the U.S. Navy in the summer of 1918. When he returned from service six months later they hit the road again and after landing two-years’ of bookings from the Keith and Pantages circuits at $250 a week, ($3,400 in today’s money), they were married on August 11, 1919. It was little more than a marriage of convenience - the couple separated in 1922 and divorced in 1928. (2)

Winchell’s career as a journalist - without portfolio or pay - began in February, 1920, when the first of his columns, Stage Whispers by The Busybody, appeared in Billboard. That led to Daily Newssense, a backstage sheet of vaudeville gossip.

He sent samples of Newssense to the Vaudeville News, an eight-page house organ of Edward Albee’s National Vaudeville Artists, a 12,000 member “union” controlled by theater owners and managers. His submissions soon became regular features titled Pantages Paragraphs and Merciless Truths.

Finally, in November, 1921, he was hired by the Vaudeville News for $25 a week, ($330 in today’s money). The 24 year old ex-hoofer had become a professional columnist Nevertheless, he had to supplement his income by selling ads in the trade paper.

Winchell’s big break came three years later when he was hired as a columnist and drama critic for Bernarr Macfadden’s New York Evening Graphic for $75 a week. It was a cut in pay for Winchell who had become a successful advertising salesman for the Vaudeville News, but it was his opportunity to write for a New York daily newspaper and that was more important than money.

The tabloid Graphic, funded by profits from Macfadden’s successful magazines, Physical Culture and True Story, had gained the dubious reputation as the epitome of yellow journalism. Your Broadway And Mine by Walter Winchell, full of gossip and slang, debuted on September 20, 1924, and fit right in. Variety founder-publisher Sime Silverman and nightclub hostess Texas Guinan became Winchell's mentors and the main sources of tips for his column as he developed new informants among the city‘s scores of press agents. Winchell became the star of the paper and his column was a “must read“ for gossip hungry New Yorkers.

Winchell’s growing fame led to his first appearance on radio in the fall of 1928 - a Will Rogers “campaign” broadcast promoting his mock presidential candidacy. A few months later in January, 1929, the columnist “conducted a tour of Broadway” on the 42 station NBC network and followed that with appearances on Rudy Vallee’s Thursday night Fleischmann Yeast Hour on NBC at $250 each, ($3400 in today‘s money). Vallee, a shrewd judge of talent, encouraged Winchell to pursue a broadcasting career. (3)

Despite his importance to the paper, internal politics caused the Graphic to fire Winchell in May, 1929. (4) William Randolph Hearst immediately signed the columnist for his morning tabloid, the New York Daily Mirror, luring him with an undisclosed signing bonus, $500 a week and 50% of the column's gross syndication revenues distributed by Hearst‘s King Features. With much fanfare Winchell's first column appeared in the Mirror on June 10, 1929

The Great Depression was looming but nothing would stop the growth of Winchell’s career and wealth. The columnist had himself become a colorful character, roaming Broadway after dark, befriending politicians, show people and gangsters, holding court for press agents and their clients every night in the Cub Room of the Stork Club and racing around until dawn in his police radio equipped car. Before long, he established working and living quarters at the St. Moritz Hotel and seldom went near the Mirror's offices.

Much to the chagrin of the journalism establishment, Winchell’s columns on page ten of the Mirror stringing together unrelated items of sensationalized news and gossip separated by ellipses and flavored by his metaphoric slang became wildly popular.

Terms like ankle, (to leave), a blessed event or storked, (having a baby), Chicagorilla, (a Chicago hoodlum), debutramp, (a girl with loose morals), giggly water, (liquor), Hard Times Square, (Depression-era Broadway), infanticipating, (expecting a baby), Joosh, (Jewish), Lohengrinned or middle-aisling, (getting married), Main Stem, (Broadway), moom picher, (a movie), phewd, (a smelly feud), phfft!, (a breakup), revusical, (a musical), radiodor, (a bad radio show), pash, (passion), Reno-vated, (divorced), shafts, (legs) and vomics, (dialect comedians), became models for his many imitators.

Marlen Pew, editor of the journalism trade magazine Editor & Publisher, wrote of the Winchell-led breed, “In fact, much of the stuff is faked or guessed. Other matter is dirt no respectable writer would put on paper. It is a dirty business.” Nevertheless, syndication money for Winchell’s column poured in from “respectable” papers all across the country.

CBS owned WABC/New York was first to capitalize on Winchell’s notoriety on Monday, May 12, 1930, with a weekly 15 minute gossip chatterfest sponsored by Saks Department Store at 7:45 p.m. The show was called Before Dinner, but then - possibly looking at the clock - it was renamed Saks Broadway With Walter Winchell. As quoted in the Gabler biography, he opened his first broadcast with, “I’m the Peek’s Blab Boy who turns Broadway’s dirt and mud into gold.” Saks cancelled the show in August but by that time Winchell had filmed his first Warner Brothers/Vitaphone short, The Bard of Broadway, and he was hotter than ever.

Hearst recognized his importance to newspaper circulation and gave him a new five year contract in September worth an estimated $121,000 per year. At mid-month he began a new Tuesday night radio series for Wise Shoe Company on WABC worth another $1,000 a week. Adding to his bank account in January, 1931, he emceed a stage show featuring Harry Richman and Lillian Roth at New York’s Palace Theater that paid him $3,500 for the week’s work. ($54,880 in today’s money). As he explained, “You can take the boy out of vaudeville but you can’t take vaudeville out of the boy.”

Winchell segued into his third WABC show on September 15, 1931, The quarter hour Tuesday night series for La Gerardine Hair Wave Cream for women was similar to the Wise program. Winchell's gossipy items were sandwiched between performances by his guest stars who, over the first month, included Kate Smith, Cab Calloway, Morton Downey and the Mills Brothers. Winchell also became friendly with Ben Bernie whose band followed the La Gerardine program on WABC and that led to good natured jibes between the two. Their paths would cross many times again.

Winchell’s fast paced 15 minute local variety show became popular with listeners - and one listener in particular: American Tobacco’s CEO, George Washington Hill. Hill was scouting for a new host for his hour long Lucky Strike Dance Orchestra broadcasts on NBC three nights a week.

As he proved in the case of Jack Benny in 1944, whatever George Washington Hill wanted, George Washington Hill got He offered La Gerardine an incredible $35,000, ($540,500 in today‘s money), just to let Winchell appear on the Lucky Strike show for a month, while his Lord & Thomas advertising agency sampled listener reaction..

On Tuesday, November 3, 1931, Winchell did the La Gerardine show with Ruth Etting on WABC at 8:45 for 15 minutes, then raced over to NBC’s studios for his first Lucky Strike Dance Orchestra broadcast featuring Wayne King’s band at 10:00. That, plus the Thursday and Saturday night Lucky Strike shows, became his routine for the next seven weeks as he “auditioned” for George Washington Hill and scrambled to find his successor to host the La Gerardine show.

Winchell left the WABC program on December 15th and a month later the replacement he recruited - a 30 year old sportswriter turned Broadway columnist from the Evening Graphic - took over. As a result, the La Gerardine show of January 12, 1932, was the beginning of Ed Sullivan‘s 39 year radio and television career.

Winchell’s contract for the Lucky Strike broadcasts called for $3,500 a week - among the top salaries in Network Radio. Coupled with his Hearst column and syndication income he was making over $6,000 a week, ($102.800 in today‘s money). By the spring of 1932, Lucky Strike had 45,000 billboards across the country and full page magazine ads featuring Winchell. Whether listeners liked him or not, Lucky Strike had made him a national figure.

And not everyone liked Winchell. He had the protection of his friend, gangster Owney Madden, but he claimed that death threats had become routine in 1932, particularly after Vincent Mad Dog Coll was gunned down by Madden’s henchmen in February. He blamed the overwhelming pressure of impending doom to cause his collapse after the Lucky Strike broadcast of April 16th.

Winchell left for California to recuperate and while there agreed to film Okay, America!, (his Lucky Strike catch-phrase), for $50,000 at Universal. A month later he reneged on the handshake deal, held out for $100,000 and returned to New York. He resumed his newspaper column in the Mirror on June 1st and the Lucky Strike broadcasts on June 16th although comedian Walter O’Keefe had taken over as host of the program during his absence. Two months later Winchell suffered another questionable collapse and left the program permanently. (5)

How sick was he? During September Winchell agreed to a contract with Universal to appear in 13 filmed shorts - although the number turned out to be only two - 1933’s I Know Everybody & Everybody’s Racket and Beauty On Broadway. He also wrote the story for the movie Broadway Thru A Keyhole based on Al Jolson’s courtship of dancer-actress Ruby Keeler, which earned him a reported $30,000 and a highly reported punch in the nose from Jolson.

During his “illness” Winchell also produced his daily column and negotiated what turned out to be his radio contract of a lifetime with the Andrew Jergens Company for a 15 minute newscast every Sunday night on the Blue Network.

He hit the air running with the Jergens Journal on Sunday, December 4, 1932, at 9:30 p.m, scoring an 8.7 Crossley rating for the month. His average rating for the season was 11.6, edging out American Album of Familiar Music’s 10.0 on NBC, his only rated competition in the time period. Winchell’s 44th place finish among all programs was his first of 21 consecutive Top 50 finishes - a feat matched only by Jack Benny.

Poised in shirtsleeves, loosened tie, belt and fly, and wearing his trademark fedora, Winchell attempted to launch every Jergens Journal with a “Flash!” news item - the more sensational the better. That was followed by a staccato-delivered barrage of news, gossip and human interest items, each begun with Winchell barking out its dateline which seemed to elevate the most obscure divorce notice to the level of world importance. Everything but Winchell’s opinion pieces were breathlessly delivered at breakneck speed and separated by the audio version of his columns’ ellipses, brief bursts of telegraph key rattle.

Winchell considered the most important part of every broadcast to be its final item, “The Lasty.” Delivered every week with “Lotions of love…” the cleverly written human interest or opinion piece was the “kicker” to each show. Winchell and his longtime ghostwriter, Herman Klurfeld, would consider up to a dozen or more lines before settling on each week‘s “Lasty”. From its opening to its close, the Jergens Journal was unlike anything else on the air - and that’s exactly what Winchell wanted.

Winchell was outside the boundaries of 1933’s Biltmore Agreement which established the Press Radio Bureau and its stringent limits on radio news because he was considered a “commentator" not a “newscaster". As a result, he had virtually no network competition for breaking news on weekends during the much of the 1930’s.

He also began a string of 21 straight seasons of Top Ten finishes on Sunday night - another accomplishment he shared with Benny. Nevertheless, Winchell had a seven year battle for 9:30 Sunday time period leadership with American Album of Familiar Music, losing two of the first three before taking command

An unabashed fan of J. Edgar Hoover’s gang-busting FBI and the populist politics of the newly elected President Franklin Roosevelt in both his columns and broadcasts, Winchell turned his attention from the trivial affairs of Broadway to national concerns. (6) Hoover responded with friendship and influence, both of which proved useful when the “Story of The Decade” - to that time - broke in September, 1933.

The tracking and arrest of Bruno Hauptmann for the kidnapping and murder of the Lindbergh baby became Winchell’s obsession. He made it his story, receiving both plaudits and scorn for his investigative work as the authorities closed in on Hauptmann. Hoover later publicly praised “a certain well-known columnist” for sacrificing an international scoop by not divulging confidential information that led to Hauptmann’s arrest. Jergens rewarded its “certain well-known columnist” with a new contract in May, 1934 - 39 weeks at $2,000 a broadcast.

When Hauptmann’s trial began on January 3, 1935, Jergens had upped Winchell’s salary to $2,500 a week and agreed to indemnify him against any damages awarded for libel, slander, invasion of privacy or copyright infringement. He sat smiling in a front row seat while all of the prospective jurors were asked if they had ever read a Walter Winchell column or heard any of his radio broadcasts. It was the kind of publicity that money couldn’t buy and Winchell’s ratings jumped nearly 30% during the trial,

Once the trial was over Winchell’s ratings sank back into the single digits in the 1935-36 season. Meanwhile, his old pal from WABC, Ben Bernie, was having his own problems. His new sponsor, American Can Company, moved The Old Maestro and his band from their three highly rated seasons on NBC to the Blue Network and brought about a 47% loss of audience.

Winchell and Bernie got together and created Network Radio’s first famous “feud” - cross-promoting each other with insults on their programs. It never reached the proportion of the Jack Benny/Fred Allen “feud,” but did result in two 1937 20th Century Fox films starring the pair as themselves: August’s Wake Up & Live and Love & Hisses in December. To promote the two movies, Winchell starred in Lux Radio Theater’s adaptation of The Front Page in June.

The notoriety of the two films got Bernie a new show on CBS with double digit ratings and helped solidify the Jergens Journal as a Top 20 show for three consecutive seasons through 1938-39 and pushed Winchell‘s weekly salary from his grateful sponsor up to $5,000.

Winchell made news on his own in August, 1939, by ending the 21 month manhunt for murderer Louis Lepke Buchalter who surrendered himself to the columnist, “The one person I can trust.” Winchell turned the killer over to J. Edgar Hoover but turned down the $50,000 reward offered for the fugitive’s capture, calling it his “gift to the people.”

Two other factors, however, played a greater role in Winchell’s pending success of huge proportions. His broadcasts had been evolving since the Hauptmann trial to more hard news and less trivial gossip. Winchell was a hawk - known in the prewar days as an “Interventionist”- who continually warned his listeners of the dangers if America wasn’t prepared to defend itself against the rise of fascism. The outbreak of war in Europe in late 1939 pushed his ratings up 38% and into the 20’s.

Of secondary importance, his Sunday night program was moved back from 9:30 to 9:00 p.m. ET in 1939. Historically, most of the Annual Top Ten programs started on the hour, not the half-hour. True to that form, Winchell scored his first of eight consecutive seasons in the Annual Top Ten in 1939-40. The program remained at 9:00 for 15 years, registering an overall total of twelve Top Ten finishes. (7)

He broke into the twenties in 1940-41 with a season average of 24.1. Four episodes of the Jergens Journal from the 1940’s are posted: May 18, 1941, February 25, 1945, April 22, 1945 and May 6, 1945. Listeners will pardon the poor audio quality but the recordings provide examples of the hectic pace Winchell set. By comparison, conversationally paced newscaster Lowell Thomas registered a season average of 14.2, H.V. Kaltenborn an 11.6 and Gabriel Heatter a 7.4. Then came Pearl Harbor.

Winchell’s Sunday night broadcast of December 7, 1941, fell within a Hooper survey week. The saber-rattling columnist suddenly became the prophet patriot and scored his highest single broadcast rating to date - a 29.9. (The poor recording of the broadcast is also posted below.) His January and February ratings climbed even higher to 33.1 - territory normally occupied by only the most popular variety shows. Not even the return of Fred Allen to a CBS variety hour opposite Winchell in mid-March could slow his ratings momentum. At 26.0, his 1941-42 average was the highest of his 21 consecutive Top 50 seasons.

After much pleading for active war duty to silence his critics, Winchell, who was a 45 year old Lieutenant Commander in the U.S. Navy Reserve, was called to service in late December, 1942. His assignment was simply a fact-finding mission to Brazil for the State Department, but the month in South America was enough to give him bragging rights as a uniformed veteran. The month away from his program didn’t harm the Jergens Journal’s ratings - just the opposite. Winchell’s numbers increased by approximately ten percent when he returned to the air in February.

The Jergens Journal was easily the most enduring and highest rated program ever originated by the Blue Network, peaking at Number Four as World War II neared its end in 1944-45, the only season when it was also Sunday’s most popular program, edging out perennial leaders Edgar Bergen and Jack Benny. (8)

After a down season in 1947-48 when the Jergens Journal slipped to 30th in the Annual Top 50 with nearly a 20% loss of audience, Winchell bounced back into the Top Ten in 1948-49 with almost a 30% gain and leading all programs in the February, March and June monthly ratings - the most monthly wins an ABC program would ever earn. (See The Monthlies on this site.)

Nevertheless, after a successful 16 year association, Jergens Lotion and Walter Winchell parted company in December, 1948, ending one of the longest sponsor-program relationships in prime time radio.

The columnist - reported to be another target of the CBS talent raid - became radio’s first “Thousand Dollar A Minute” star when he signed a widely publicized 90 week, $1.35 Million contract with Kaiser-Frazer automobiles after Jergens dropped out.

Winchell’s first broadcast for the auto maker in January, 1949, scored a 29.7 Hooperating but Kaiser-Frazer saw no significant sales results from the programs and opted out of the lavish contract after 26 weeks, just as Winchell was coming off his second Top Five season - a season that was punctuated with the death of an “enemy”...

Winchell was a strong proponent of the late FDR, but wary of the policies of President Harry Truman which he considered weak. In particular, he raged against the anti-Zionist stance of the country’s first Secretary of Defense, James Forrestal, a wealthy Republican. Winchell joined forces with Drew Pearson, another columnist/commentator foe of Forrestal, and unleashed non-stop attacks on the secretary, contributing to his forced resignation from Truman’s administration and letting up only when the hospitalized former cabinet member jumped to his death from the 16th floor of the Bethesda Naval Center on May 22, 1949. Two days later both Winchell and Pearson were denounced in Congress for contributing to Forrestal’s suicide with their relentless personal attacks.

Winchell seemed to overlook Forrestal’s early warnings of the menace Communism posed to postwar America - the same stance he took in his columns and broadcasts since before World War II. When war broke out in Korea 13 months after Forrestal’s death, Winchell turned his attacks to President Truman, especially after the firing of General Douglas MacArthur from his U.N. Korean command post in April, 1951. Winchell’s rebukes of Truman were so strong that many of his left-wing allies began to question his loyalties to the Democrats that were forged in the early days of the New Deal.

Listener loyalty was another question. Now under the sponsorship of William Warner Company’s Richard Hudnut Cosmetics, Winchell’s 21.7 average rating in 1948-49 sank almost 25% to 16.3 in 1949-50. But during a season when television gobbled up radio audiences by the millions and the average Top 50 Network Radio program lost 30% of its ratings, Winchell’s loss of some five million listeners every week was considered tolerable.

Hudnut and ABC which were both trying to talk their reluctant 53 year old star into simulcasting his Sunday night program on ABC’s fledgling television network. But Winchell didn’t want to be tied down to a New York television studio every week - Miami Beach had become his second home and playground in the winter. He also feared that he’d be competing against his own radio show which was still Number Six in the Annual Top Ten and second only to Jack Benny on Sunday nights.

In February, 1950, Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy claimed to have a list of 205 Communists who had infiltrated the State Department. It was the kind of material that Winchell had been seeking to substantiate his fears and warnings, but had been unable to find. Winchell met with McCarthy for two hours at the Stork Club during the summer and solidified their friendship of purpose and convenience. McCarthy and his subordinate, Roy Cohn, both knew how to push Winchell’s buttons and enlist him as an ally.

Winchell proudly proclaimed himself - like McCarthy - a “crusading commie fighter,” and began to fling innuendo-laden accusations with abandon in his columns and broadcasts. Newspapers began to severely edit or drop his syndicated columns altogether. His list of formidable critics and enemies grew to include leaders of both political parties, the NAACP and most every other influential syndicated columnist. Winchell found himself in a constant state of self-created public and private battles. But he considered himself to be a good soldier in Tailgunner Joe’s army fighting Communism and he was proud of it!

Winchell’s loss of audience continued to mirror Network Radio’s nighttime declines in 1950-51. His season rating of 12.4 was the lowest since 1935-36, yet enough to remain seventh in the Annual Top Ten and fourth on Sundays behind Jack Benny, Edgar Bergen and Amos & Andy. When the 1951-52 season began, ABC relented on its insistence that Winchell simulcast his Sunday night radio show, gave him a lifetime “consultancy” contract worth $1,000 a week and upped his pay to $8,000 per broadcast. In addition, Warner-Hudnut gave him 10,000 shares of company stock.

Winchell had made many enemies over the years - some of them sued him, others just feared him and his competitors resented him. Black chanteuse Josephine Baker tried got even with him for criticizing her denouncing American citizenship in 1936 to become a citizen of France. On her return to New York in October, 1951, she inflated an alleged case of discrimination at the Stork Club into headlines, contending that the incident, (very poor service), happened in Winchell’s presence and with his tacit approval, although he and witnesses claimed that he had left the nightclub earlier.

New York City officials found no case for discrimination, but Baker pursued it with a $400,000 defamation suit against Winchell and took her cause to Barry Gray’s late night interview show on WMCA/New York. Playing David to Winchell’s Goliath, Gray eagerly provided a microphone for Winchell’s enemies. By now that list included Ed Sullivan, who proclaimed, “I despise Walter Winchell because he symbolizes to me evil and treacherous things in the American set-up.” (Sullivan apparently forgot that the man he despised gave him his start in broadcasting.)

With the momentum of local New York columnists and commentators ganging up on Winchell with what they considered to be well deserved comeuppance, the New York Post began a unflattering 24-part series on Winchell’s life and career on January 7, 1952.

Less than three weeks later, on January 27th, Winchell closed his broadcast by claiming that his doctors had ordered him to take a month’s rest from, “all professional activities.” The Post suspended its series while he recuperated.

He returned to the air on March 9th, The Post series resumed on March 10th and Winchell promptly suffered a relapse in the midst of his twelfth and last Top Ten season, leaving the air before his March 16th broadcast. Winchell’s broadcasts were covered following his departure by Erwin Canham and Taylor Grant before Drew Pearson took over for the rest of the season in April. Despite his prolonged absences, Winchell’s 9.2 rating clung to ninth place in the Annual Top Ten and his show was still the fourth most popular on Sunday nights.

Nevertheless, Hudnut Cosmetics had enough of their star’s tantrums and traumas, cancelling its $500,000 annual sponsorship contract after three turbulent seasons.

Winchell returned to the air on October 5, 1953, seemingly refreshed after his six month leave of absence with a new sponsor, Gruen Watches. The Gruen contract called for an ABC-TV performance of his radio script on Sundays at 6:45 p.m. ET and his regular radio show at 9:00.

Two months later the New York Post filed a $1.5 Million libel suit against him, ABC, Hearst Newspapers, King Features and Gruen. It was the culmination of the eleven month feud ignited by The Post’s series that was highly critical of Winchell’s methods and ethics. In angry response, Winchell accused The Post, its publishers and editors of Communist leanings referring to the rival tabloid as, “That pinko-stinko sheet,” “The New York Pravda,” and “The New York Com-post.” Winchell’s continued smears against the paper and its editor James Wechsler, ("that former Commie”), in his newspaper columns and radio commentaries, led The Post to take their fight into court. Winchell promptly countersued for $2.0 Million and a lengthy, costly two year court battle began.

As Network Radio’s Golden Age came to a close, Winchell’s fear that his television show would cut into his radio popularity came to pass. His radio ratings plunged 40% over the 1952.-53 season. His Top Ten ranking of four consecutive seasons dropped to a tie for 36th place. He still remained in Sunday’s Top Ten but tied in his timeslot with the prestigious Hallmark Playhouse on CBS which became the Hallmark Hall of Fame at mid-season.

Winchell’s Sunday night program became a simulcast in September, 1953, but Gruen wanted to distance itself from The Post lawsuit and cancelled its sponsorship in December. His television and radio ratings were dismal and hardly worth the $520,000 that ABC was paying him.

The Post won its lawsuit two years later - settling for $30,000 in court costs and a retraction/apology from Winchell. The settlement was paid by ABC and Hearst. But the obstinate Winchell refused to say a word about the verdict. An ABC staff announcer was assigned read the apology on his broadcast of March 16, 1955..

Winchell’s penalty came three months later - the loss of his high paying ABC contract, ending his 23 year run on the network. He bid goodbye to his ABC audience on June 26, 1955, and was replaced the following Sunday - July 3, 1955 - by the network’s promising young newscaster, 36 year old Paul Harvey.

Winchell moved on to Mutual for the next two years. By that time it was open season on the columnist. Burt Lancaster’s scathing portrayal of the loathsome J.J. Hunsecker - an obvious caricature of Winchell in The Sweet Smell of Success - hit the screens shortly after Winchell left Network Radio. His last broadcast was on March 3,1957.

Six years later, on October 15, 1963, the New York Daily Mirror folded after a lengthy strike and Winchell was moved to Hearst‘s afternoon Journal-American. The paper cut his column back to three times a week and his syndication income dwindled to a fraction of its former figures. Hearst finally terminated its 38 year association with Winchell on November 30, 1967, and the once loudest voice in American journalism was silenced.

“…and so, with lotions of love, this is your New York correspondent Walter Winchell who knows that Broadway is a mountain…tough sledding on the way up and a toboggan on the way down.”

(1) Winchell would often refer to himself on his Sunday night broadcasts as “Mrs. Winchell’s Newsboy.”

(2) Winchell moved in with June Magee on May 11, 1923. The couple remained common-law man and wife until her death in February, 1970. They adopted adopted a baby daughter, Gloria, in October 1923. The child died at age nine from pneumonia. A daughter Eileen Joan (Walda) was born to the couple on March 21,1927, and son, Walter, Jr., born July 26, 1935. Although the couple maintained the pretense of wedlock, they lived apart most of the time and Winchell openly kept a string of girlfriends and mistresses.

(3) Winchell betrayed Vallee in February, 1939, by planting a front page story in the Miami Herald that the popular crooner had “slugged” a busboy backstage during an engagement at the Royal Palms nightclub. Vallee was exonerated but Winchell didn’t retract his story.

(4) The Graphic went bankrupt and ceased publication on July 7, 1932.

(5) Walter O’Keefe remained with the Lucky Strike Dance Hour and returned Top Ten Crossley ratings for the Tuesday and Saturday editions of the program until it left the air in April, 1933.

(6) Roosevelt summoned Winchell to the White House shortly after his inauguration to acknowledge the columnist’s support and assure his continued loyalty. The President used their mutual friend, Democratic National Committee counsel Ernest Cuneo, as a go-between for occasional scoops and more frequently, political points he wished Winchell to push.

(7) In 13 of C.E. Hooper’s 30 surveyed cities, Winchell was broadcast on the local NBC station.

(8) Winchell’s broadcasts were heard twice every Sunday on the West Coast from December 2, 1945, to December 25, 1949. The Blue/ABC affiliates carried the first feed at 6:00 p.m. PT and the Don Lee Network carried the second feed at 8:30.

Copyright © 2015 Jim Ramsburg, Estero FL Email: [email protected]

| w_winchell_05-18-41.mp3 | |

| File Size: | 10761 kb |

| File Type: | mp3 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| w_winchell__04-22-45.mp3 | |

| File Size: | 10171 kb |

| File Type: | mp3 |

| w_winchell_05-06-45.mp3 | |

| File Size: | 10265 kb |

| File Type: | mp3 |

| lux_radio_theater__the_front_page__37-06-28.mp3 | |

| File Size: | 14027 kb |

| File Type: | mp3 |